The August 16, 2025 worship service of Bethlehem Christian Church, Suffolk.

Colonial Virginia

Good Friday, Hot Cross Buns and Bermuda

Wishing all a blessed Good Friday, and a double dose of #fredonhistory

I had never seen or heard of a “Hot Cross Bun” – spiced buns with mixed fruit and topped with an icing cross – until my travels and research took me to Bermuda 🇧🇲 . One bit of folklore attributes these to have originated in 16th/17th England, due to a ban on the sale of spiced baked goods during Easter and Christmas. Apparently a resourceful baker decided if such buns were “blessed” with a cross it would get around such prohibitions by making their sale one with a religious connotation.

Whatever the origins though, generally after Lent all I have on my mind is the taste of these spicy, fruity, and sweet delectable treats. And in recent years, I am thankful they have made their way to the States.

Today, I was fortunate to find a pan of fresh Hot Cross Buns at Yummaries Bakery in Smithfield.

Which brings me to another bit of history.

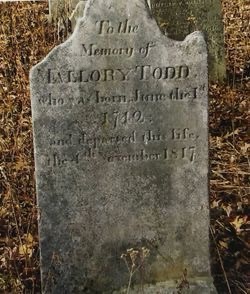

The Town of Smithfield also has multiple Bermuda connections. Those who know a little something of Smithfield history will recognize the name Captain Mallory Todd and the stately “Todd House” (aka Nicholas Parker house, built in 1750s) located on Main Street.

Mallory Todd, a noted seaman and merchant, was in fact a native of Bermuda and is believed to have come to Smithfield in the 1760s (likely joining another branch of his family, also Bermudian – the Mallorys) to pursue a variety of financial opportunities in the colonies. In the midst of the Revolutionary War, Todd expanded his business, and is credited as being the father of our famed “Smithfield ham” – curing them so that they would be preserved during their export across the Atlantic to England, Bermuda, the Caribbean, and abroad.

So today, while I enjoy my hot cross buns and reflect on the solemnity of Good Friday, I am also mindful of the great irony that these same Smithfield-made cross buns were likely being enjoyed by the Mallory and Todd families some 250+ years ago as well.

And that little idea of Captain Todd’s – curing and shipping local hams 🐖 – well it seemed to take off pretty well, too!

The Parker/Todd House, along Main Street, Smithfield, Virginia

The 250th Anniversary of South Quay Baptist Church

I had the distinct privilege of speaking at the homecoming celebration held on Sunday, March 16, recognizing South Quay Baptist Church for its 250th anniversary. It was a packed-house, with standing room only and just a wonderful day of sharing history, fellowship, and worship!

The pictures below are courtesy of South Quay’s Facebook page.

Additionally, the following resolution was passed by the Senate of Virginia as SR219 commending South Quay on this great honour and outlining the Church’s history:

Offered January 23, 2025

Commending South Quay Baptist Church.

—————

Patron—Jordan

—————

WHEREAS, South Quay Baptist Church of Suffolk, one of the oldest Baptist congregations in the Commonwealth, will celebrate its 250th anniversary on March 1, 2025; and

WHEREAS, South Quay Baptist Church was a mission church of Mill Swamp Baptist Church and located originally along the Blackwater River on the border of Southampton and Nansemond Counties; the church was organized with a bi-racial congregation of 42 members on March 1, 1775, under the leadership of the Reverend David Barrow, a noted anti-slavery and liberty advocate; and

WHEREAS, South Quay Baptist Church moved to its current location in then-Nansemond County in 1835, becoming commonly known as “Reedy Branch Church” due to its location along Reedy Branch in the South Quay community; and

WHEREAS, during the Civil War, by order of Governor William Smith, South Quay Baptist Church served as the temporary courthouse for Nansemond County during its military occupation between 1864 and 1865; and

WHEREAS, the Reverend Putnam Owens of South Quay Baptist Church ordained former slaves Israel Cross and Joseph Gregory, both members of the church, who went on to establish Cool Spring Baptist Church, now First Baptist Church of Franklin, in 1866 and Mount Sinai Baptist Church located in Nansemond County in 1868; and

WHEREAS, South Quay Baptist Church, in the wake of Reconstruction, erected a new building in 1889 after the church was destroyed by a fire, and said building comprises today’s present church building; and

WHEREAS, over the course of time, South Quay Baptist Church has greatly expanded in membership and completed a parsonage, fellowship hall, and Sunday school classrooms to better serve the growing community; and

WHEREAS, South Quay Baptist Church has provided the community uplifting spiritual guidance, proclaiming the word of the Lord and encouraging deep, personal relationships with Jesus Christ, and these efforts have been complemented by joyful occasions for worship, fellowship, and abundant opportunities for charity and outreach, making the church an integral and cherished part of the City of Suffolk and Southampton County; now, therefore, be it

RESOLVED by the Senate of Virginia, That South Quay Baptist Church hereby be commended on the occasion of its 250th anniversary; and, be it

RESOLVED FURTHER, That the Clerk of the Senate prepare a copy of this resolution for presentation to South Quay Baptist Church as an expression of the Senate of Virginia’s high regard for the church’s history, heritage, and contributions to the Commonwealth.

Celebrating the Return of General Lafayette

Today, I am still reveling in the excitement of the at-capacity, 250+ person banquet commemorating the February 25, 1825, visit of General Lafayette to Suffolk.

We were blessed to have the General himself – portrayed by the talented Mark Schneider, and numerous dignitaries locally and abroad, the Mayor and members of City Council, French military personnel, Virginia American Revolution 250, scholars of the The American Friends of Lafayette, Daughters of the American Revolution, and so many more!

Of course, it would take such a significant event to cause me to abandon my beard of years, in order to channel my inner 1820s gentleman! Not the least of which was the high honour of serving as the Master of Ceremonies for a wonderful evening of history, and the celebration of our timeless bond with France.

Viva la France & General Lafayette!

Back in Brunswick County

Channeling my inner “Professor” to talk Brunswick County history with the Lake Gaston Ladies Club.

Pea Hill Plantation History Revealed

Thanks to the Lake Gaston Gazette for covering this program!

Hometown History with WTKR

We love our “Folly” – thanks to Myles Henderson at WTKR News 3 for sharing our great story!

Here is the link:

What’s in a Name? The Search for Lewis B. Taylor of Brunswick County, Virginia

By Fred D. Taylor

For decades, a number of Taylor family researchers have worked tirelessly to determine the parents of Lewis B. Taylor of Brunswick County, Virginia, who was born circa 1772 and died before December 1831.

When my father and I first began our own family tree quest in the early 1990s, this mystery was a source of almost heated debate among our cousins, spanning from family researchers very close to the source in Brunswick County, all the way out to the West Coast, and everywhere in between. To say the search was both dedicated and committed is an understatement. Countless hours were spent by dozens of individuals in libraries and courthouses across Virginia and North Carolina in hopes of untangling this genealogical roadblock. From there, professional genealogists were employed to put an independent set of eyes on the project. When that failed (or rather, did not succeed), researchers in the family decided a new route – that of DNA testing, at that time (the mid 2000s) a research tool in its infancy.

Through all of that, the ultimate goal of learning more about Lewis B. Taylor, and more importantly his parents, remained elusive. During this time and up to recent years, I remained in the peripheral of this research, occasionally touching base with family across the country to see if they had uncovered any new leads of interest. We also discussed the DNA aspect, as it was becoming trendy, but that seemed to be nothing more than the latest rabbit hole for genealogists.

For some years, I remained out of the loop, but in 2013 decided to renew my own research on the family. My first objective was to not simply rely on everyone else’s records, or rather, their assumptions about certain information. This is something I see all too often in the genealogical world. Instead, I wanted to find the actual documentation of a certain fact, or at least be able to back-track a source to its origin. The best example I can offer in this scenario is the name itself of our subject, Lewis B. Taylor. For years, I had been told that his full name was Lewis Ball Taylor. However, when it comes to the records for him, no court record, legal document, or other period account supports this. Instead, what we find is Lewis B. Taylor or Lewis Taylor or L.B. Taylor. So where did the Ball name come from? From what I can now tell, it came from an assumption within the family that the “B.” in Lewis B. was Ball, because of the fact that he had a grand-daughter whose name was Minerva Ball Taylor and a great-grandson named Benjamin Ball Taylor. Down the road, while we certainly may learn that Ball is his middle name, without more at this time, it is only conjecture.

But I digress from the main topic of this story.

In addition to starting from scratch on the research aspect of Lewis B. Taylor’s history, I finally convinced myself that it was time to do more with the DNA angle. At that time, there had been one Lewis B. Taylor family descendant to contribute to the Taylor Family Project at Family Tree DNA. To give those of you a little background on this project, I will quote from their website directly:

“The Taylor Family Genes Project (TFG) — with more than 700 members — is the largest and best Taylor Surname DNA project offered by any DNA testing company. For a common, multi-origin surname like Taylor, database size matters; it increases your chances of finding a match within the project. Having begun in late 2003, we have members with various DNA tests and are growing daily. Among our >550 members with more than 12 markers of Y-DNA results, we have identified ~80 genetic Taylor families and more than 300 unique haplotypes (individual family lines).”

When it comes to DNA research like this, size matters, and this project is THE project if you want to be serious about your Taylor family origins.

Unfortunately though, even with this kind of resource at our disposal, our one Taylor DNA submittal had turned up no matches to any other Taylors. Despite this, I decided that it would not hurt for me to submit as well, so at the very least we would know that our “control” subject for descendants of Lewis B. Taylor was accurate. We also decided to upgrade the test for our early DNA submission. Originally, he had only been tested at the Y-25 level, which while cutting edge at the time, was a less than helpful tool a decade later.

So what did we find out? Well, not surprisingly, our original submission and I came back as the highest matches for each other. For easier reference, I will refer to him as Taylor Test One.

To give you an idea of how this works, of Taylor Test One’s 111 Y markers tested, I tested as an exact match for 108 of them. This is highly significant, as in scientific terms it carries a 78% chance of a common ancestor within the last 8 generations and 91% within the last 10 generations. This testing also confirmed some of our “paper” genealogy, as we came from two different branches of the Lewis B. Taylor line, specifically: Taylor Test One was a descendant of William Ney Murat Taylor (1816-1896) and I am a descendant of John W. Taylor (1797 – ca. 1870s).

I will also note for you DNA nerds out there that we are labeled as Group 81 in the Taylor Family Genes Project, with the R1b group designation, and the R1b1a2 sub-clade. Advanced Y-DNA testing also has the ability to dig beyond the R1b1a2 designation into further sub-classes, and specific SNP mutations that we share with smaller groups of people. Think of it as a family tree descendancy chart. Now I can go into a lot more detail here about the various sub-clades (and their designations) that we match up to (there are thousands), but at the end of the day, our classification comes down to a group designated as Z-253 and below that, FGC3222. [Now, end of the scientific/DNA details.]

Unfortunately, while our DNA testing (at this point) has turned up no other direct Taylor family matches, it has allowed us to start eliminating some other Taylor families who resided in and around Brunswick County in the 18-19th Century. This is a biggie for genealogical research, as it allows us to exclude some of those rabbit holes we had been chasing for decades. So here is who we are NOT related to or descended from:

- The Edward Taylor (1722-1784) and Jesse Taylor (1752-1800) Families of Brunswick County… In a prominent and often cited discussion on Genealogy.com, Taylor family historian Ed Dittmer theorized that Lewis Ball Taylor could be a son of Jesse Taylor. This was a great lead, based on the dates, location, and the fact that LBT had a son named Jesse. However, DNA data proved this to be incorrect, as confirmed “paper” genealogy and later DNA showed that descendants of Jesse Taylor (specifically, Jesse Major Taylor (b. 1798) and George Edward Taylor (b. 1797/98)) are from the Y-DNA group I-M253. They have been separately designated in the Taylor Family Genes Project as I1-001 Group 01, and appear to descend from Robert Taylor of Rappahannock County, Virginia, circa 1688. See http://www.taylorfamilygenes.info/groups/grp_001.shtml for more information about this line.

- The Thomas Taylor (1750/60–1820) and Benjamin Taylor (1780-1853) Families of Lunenburg, Brunswick, and Mecklenburg Counties and Elsewhere… Again, another prominent family that we originally believed that LBT may have had a connection to due to ages and similar family names. Upon the submission of a Y-DNA sample from a descendant of this line, however, it was determined that this line has a Y-DNA of I-M270, and appear to descend from the Rev. Daniel Taylor, Sr. (ca. 1664-1729) of New Kent and King William Counties, Virginia.

- The James Taylor, Jr. (1770-1827) of Mecklenburg Family. This was another potential “hope” of ours, as this family spread across Brunswick and Mecklenburg Counties, as well as into Halifax County, NC, in the late 18th Again, we met a roadblock, as the DNA submission from a descendant of this line determined that this family has a Y-DNA of R1b-M269, with the Western Atlantic Modal Haplotype, and have as their most distant paternal ancestor, John Taylor (1627-1702) of Northumberland County, Virginia. This line has been separately designated in the Taylor Family Genes Project as R1b-091 Group 91.

- The James Taylor (1642-1698) Family (which includes the Rev. Lewis B. Taylor of Granville County, North Carolina). This is probably the most notable of Taylor families, and the one that many Taylors claim and wish to be descended from, as this includes the lines of such notables as Presidents James Madison and Zachary Taylor, among many others. However, the reality is that very few are connected to this line, and ours is one of them that certainly is not. This line is designated as group R1b-002 Group 2 in the Taylor Family Genes Project, and more information about this line can be found at: http://www.taylorfamilygenes.info/groups/grp_002.shtml

[Note: *Currently, we are testing two possible Taylor candidates through DNA submission (and with Brunswick & Mecklenburg County ancestry), with the hope that we may find a match to our Lewis B. Taylor family line.*]

Now, where does that leave us?

Much like those dedicated researchers before us, I and many other continue on our quest to discover new information about Lewis B. Taylor. This has come with some reward. For one, we have been able to locate the lands owned by Lewis B. Taylor that were situated in the White Plains area of Brunswick County, and discovered that his home place still exists. While we do not know for sure, it is very likely that he is buried on this property.

Similarly, focused research on those period documents that relate to Lewis B. Taylor help to tell us more about the man himself, and his family. For instance, an inventory of his Estate after his death, and recorded at the Clerk’s Office of the Brunswick County Circuit Court on December 31, 1831, relate that his personal property included such items as English furniture, numerous books, pictures, and a looking glass. Based on other Court records, we also know that Lewis B. Taylor could read and write, had vast vocational skills that included carpentry and farming, and that he was very active in his community. Unfortunately, those bits of information do not answer for us where and when he was born, his family, or even details about his upbringing. Our earliest record of him comes to us from Brunswick County in 1793, so we can presume he was “of age” at that time, but we know little else.

For now, I have kept a log of “field notes” about Lewis B. Taylor, of which I share with you today in the file Lewis B. Taylor Notes – Jan 10 2016.

With this story, I hope to not only draw more interest from those already researching the Taylor family (and specifically Lewis B. Taylor), but cross my fingers that this information and that which remains to be discovered will lead us to eventually unraveling the mystery of Lewis B. Taylor of Brunswick County.

Have questions? Want to aid in the search? Please contact me! fred.taylor.va@gmail.com

Thanksgiving, A Southern Tradition Since 1619

by Fred D. Taylor, originally published November 2005 in the Suffolk News-Herald; updated November 2015.

As Thanksgiving is just days away, I decided to change the pace away from simply discussing someone of local significance or an historic battle, and talk a little about the history of the first English Thanksgiving in America.

While most school children in the last few weeks have been performing plays celebrating that spectacular gathering between the Pilgrims and the Indians, the truth of the matter is they got it all wrong. Gasp! Yes, I’m here popping the bubble of all the little kids who dressed up in their pilgrim hats and buckled shoes, or Indian headdresses, to tell the story the history books didn’t want them to know…

Despite popular American nostalgia that the first Thanksgiving was held by the Pilgrims after the arrival of the Mayflower at Plymouth Rock, it actually had its beginnings just a few miles from us along the James River at present-day Berkeley (pronounced Bark-lee) Plantation in Charles City County.

The year was 1619, twelve years after the establishment of Jamestown, when a group of thirty-eight settlers aboard the ship Margaret arrived after having made a ten-week journey across the Atlantic. Upon their landing, they knelt and prayed on the rich Tidewater soil, with their Captain John Woodlief proclaiming:

“Wee ordaine that the day of our ships arrivall at the place assigned for plantacion in the land of Virginia shall be yearly and perpetually keept holy as a day of thanksgiving to Almighty God.”

As historically recorded, this event was the first English Thanksgiving in the New World. So why the big deal about the Pilgrims and the first Thanksgiving being at Plymouth Rock? Good question. Some historians follow the trail to northern-written textbooks (after the War Between the States, of course), but even then anything more than a cursory study of colonial history will lead one to the discrepancy between the dates of the first Thanksgiving. Yet, we continue today to recognize the Plymouth Thanksgiving as the first, despite the clear evidence to the contrary. In fact, the irony of all ironies is that not only did Virginia’s Thanksgiving celebration occur before the one in Massachusetts, the Pilgrims had not even landed in America yet! The Pilgrims arrival would come one year and seventeen days later in 1620, and their Thanksgiving celebration nearly two years later in 1621.

Celebrations of “thanksgiving” would become a deeply rooted American tradition though, usually brought on by periods of great hardship. During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress proclaimed days of Thanksgiving every year from 1778 to 1784. Likewise, George Washington issued the first Presidential proclamation of Thanksgiving in 1789, and a few of his successors followed suit. Interestingly, Thanksgiving was not a specific day or even month, and apparently was issued on the whim of whoever was in office. Sporadically between the years 1789 and 1815, days of Thanksgiving were recognized in January, March, April, October, and November. This recognition of Thanksgiving ended in 1815 following the term of President James Madison, and a President would not issue such a proclamation for another forty-six years.

That President was Jefferson F. Davis, who recognized a day of thanks, humiliation, and prayer for the young Confederate States of America for October 31st, 1861. Not to be outdone, President Abraham Lincoln resurrected the forgotten day in the United States as well, and issued a similar proclamation in April of 1862. In 1863, Thanksgiving was made a national holiday, and in 1866, the tradition of recognizing Thanksgiving on the fourth Thursday of November was started by President Andrew Johnson.

From that time on, every sitting President has recognized Thanksgiving as a national holiday. Nonetheless, the twists in the story continue. While the recognition of the holiday has been uninterrupted since 1861, the explanations of the origins of Thanksgiving have been numerous. For years, the residents of the Oval Office ignored Virginia’s claim to the first Thanksgiving, but that all changed in 1963. It took a Massachusetts Yankee by the name of John F. Kennedy to take the risk of alienating his constituency back home to tell the rest of the story. President Kennedy honored Massachusetts’s and Virginia’s claim in his proclamations of 1963 at the urgency of his Special Assistant Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., a noted historian and political scientist. After Kennedy’s death, President Johnson mentioned Virginia twice, President Jimmy Carter recognized it in 1979, and the last to recognize Virginia’s claim was President Ronald Reagan in 1985.

Today, the struggle to tell the true story of Thanksgiving continues in classrooms across America, and even more so here at home in Virginia where it all started. For several years now, a group of concerned citizens have organized an annual event to celebrate the First Thanksgiving at Berkeley, and each year they recreate that historic event on the shores of the James River.

In the wake of America’s 400th Anniversary in 2007, the necessity to tell the real Thanksgiving story is all the more important. So as you prepare for Thanksgiving this year, take a few minutes to reflect on this story, and to pass this tidbit of history along to others. Every little bit helps in getting the truth out. As for me this year, I’ve certainly got plenty to be thankful for, but in honour of those courageous thirty-eight who arrived on the shores of Virginia in 1619, I’ll be substituting my turkey and stuffing for Smithfield Ham and Chesapeake Bay Oysters.