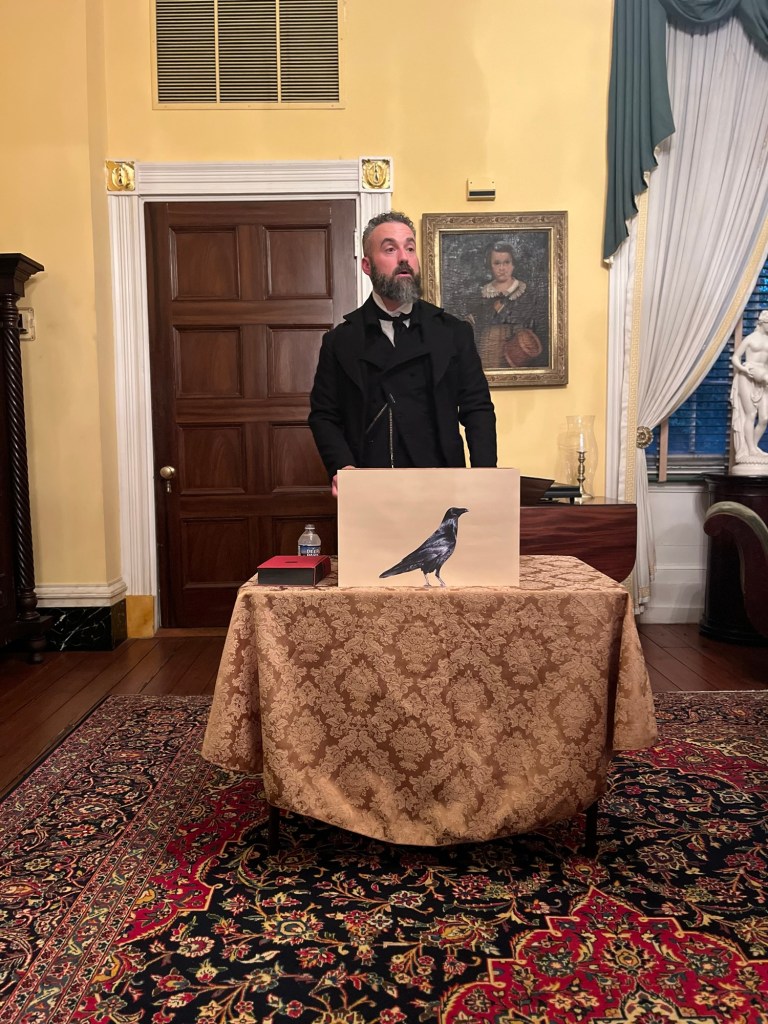

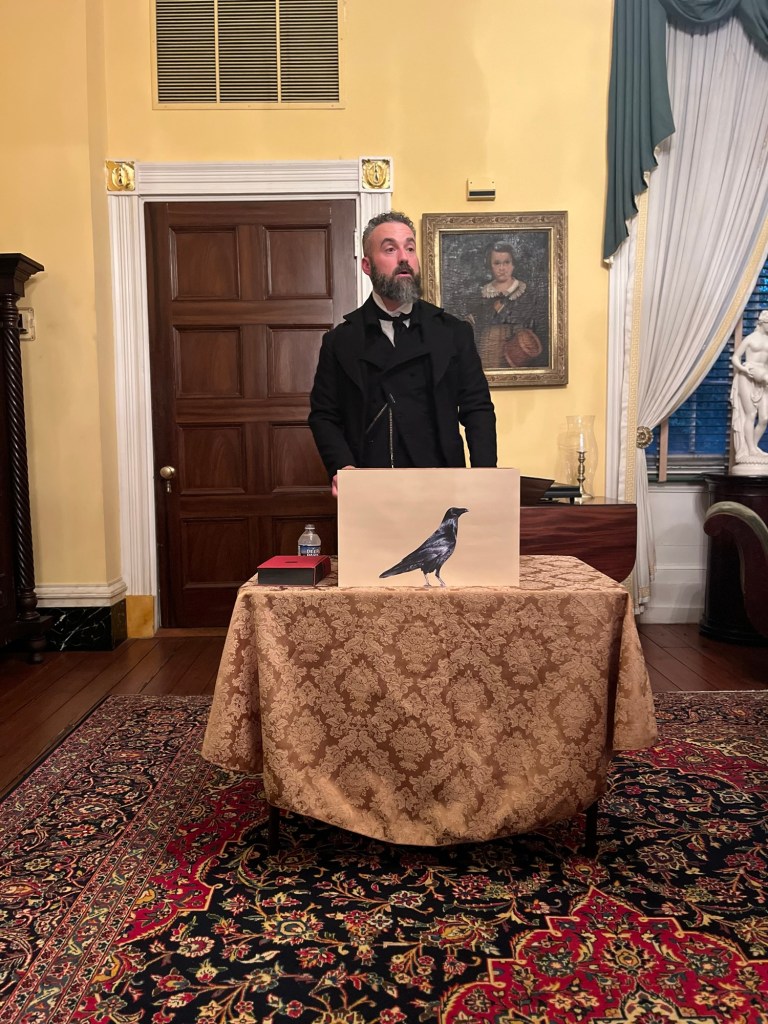

Our annual night of readings from Edgar Allan Poe at Suffolk’s Riddick’s Folly House Museum.

Our annual night of readings from Edgar Allan Poe at Suffolk’s Riddick’s Folly House Museum.

The August 16, 2025 worship service of Bethlehem Christian Church, Suffolk.

It’s throwback Thursday… and I get to talk about two of my favs, history and Bermuda! So…

🇺🇸 the 1775 Gunpowder Plot?! 🇧🇲

From a camp near Boston, on September 6, 1775, General George Washington penned a letter to the “Inhabitants of the Island of Bermuda,” calling on their “Favor and Friendship to North America and its Liberties…” Its purpose was to solicit much-needed gunpowder for Continental troops. This was a tricky request, as Bermuda had been under an American embargo some months before, and suffering from the loss of much needed food and other supply. What Washington proposed in essence was a trade.

His letter was unnecessary, though.

Much to his relief, friendly Bermudians had already come to the Colonies’ rescue just weeks before, on this day – August 14 – two-hundred and fifty years ago.

On that hot and humid night, under a full moon, several dozen Bermudian patriots under the guidance of Colonel Henry Tucker (father of Virginian, St. George Tucker) made their way to Tobacco Bay on the northeast coast of the island, climbing a steep hill and some distance to reach an unguarded powder magazine. There they acquisitioned and removed more than 100 casks of gunpowder, transporting them back to the Bay and loading the casks on two ships ready for transport to Philadelphia and Charleston.

The mission was a success, with thousands of pounds of gunpowder readily received for use by Washington’s army . And while investigated by the loyal Governor, no charges were ever brought against any suspect for their acts.

Yesterday’s #fredonhistory post got a lot of comments, so here we go remembering day 2 of Gettysburg, with two images featuring officers of the 33rd North Carolina, one of whom fell on the field that day…

When North Carolina seceded in May of 1861, forty-three year old attorney Tod Robinson Caldwell of Morganton held strong to his allegiance to the Union. A five time member of the North Carolina General Assembly, Caldwell was said to be an old line, “Henry Clay Whig,” who could not support secession.

Without a doubt then, he also hoped his teenaged son, John “Jack” Caldwell, would do the same. Young Jack was a Cadet at the Hillsboro Military Academy at the time though, and it did not take long for him to cast his lot with the South. By September of 1861, Caldwell was serving as a 2nd Class Drill Instructor for the state of North Carolina in training camps in and around Asheville. He continued in this capacity through 1862, until most of the volunteer regiments had organized and marched off.

Reaching the age of 18 and longing to command in the field, Jack Caldwell called on his old family friend and neighbor, Colonel Clarke Moulton Avery, commander of the 33rd North Carolina Troops. When Caldwell reached the regiment in early May 1863, the 33rd (a part of Lane’s Brigade) was in action at the battle of Chancellorsville. That same day Caldwell was appointed to serve as a 2nd Lieutenant in Company E of the 33rd.

After receiving his baptism under fire at Chancellorsville, young Lieutenant Caldwell marched northward with the 33rd North Carolina in Lee’s second invasion of the north. The result was the battle of Gettysburg.

On the second day of the battle, Major General William Dorsey Pender called on the 33rd for volunteers to challenge a line of Yankee skirmishers who were wreaking havoc on their front. Seventy-five volunteered and were placed under the command of Lt. Wilson Lucas and Lt. Jack Caldwell. Lucas recalled Pender asking, “Can you take that road in front? If you can’t take it say so, and I will get someone who can.” Lucas responded, “We can take it if any other 75 men in the army of Northern Virginia can.” Lucas went on to describe:

“We formed the men in line, I commanded the right and Lieut. Caldwell the left. We had to charge through an open field, with no protection whatever… When we got within two hundred yards of the Federals, we charged with a yell, and they stood their ground until we were within ten steps of the road, then a part of them ran, but 26 surrendered. And the very last time they fired upon us, which was not more than twelve or fourteen feet from them, they shot Lieut. Caldwell in the left breast. I did not see him fall. As soon as we were in the road one of the men told me Lieut. Caldwell was killed. I went at once to the left and found him, lying partly on his back and side… I called two men, and we placed him on his back and spread his oil cloth over him. He was warm and bleeding very freely when I got to him. I could not send him out to the regiment, for it was such an exposed place the Federal skirmishers would have killed a man before he could get a hundred yards, as we were lying close to each other.”

As a result of his courage that day, Lt. Caldwell was recognized by his comrades on North Carolina’s Roll of Honor.

Following the engagement , Caldwell’s body was safely recovered and his remains returned home, where he is buried at the Forest Hill Cemetery in Morganton.

I should also add, Caldwell’s father went on to become Lieutenant Governor and Governor during the Reconstruction period in North Carolina.

Images:

1/4 plate tintype of John “Jack” Caldwell as a Cadet at the Hillsboro Military Academy. Courtesy of the Brem Family.

Carte-de-visite of Colonel Clarke Moulton Avery, M. Witt’s Photograph Gallery, Columbus, Ohio. Taken while prisoner of war at Johnson’s Island, 1862. Courtesy Fred D. Taylor Collection, Suffolk, Virginia.