A couple of new additions to my “crew” of blockade runner images.

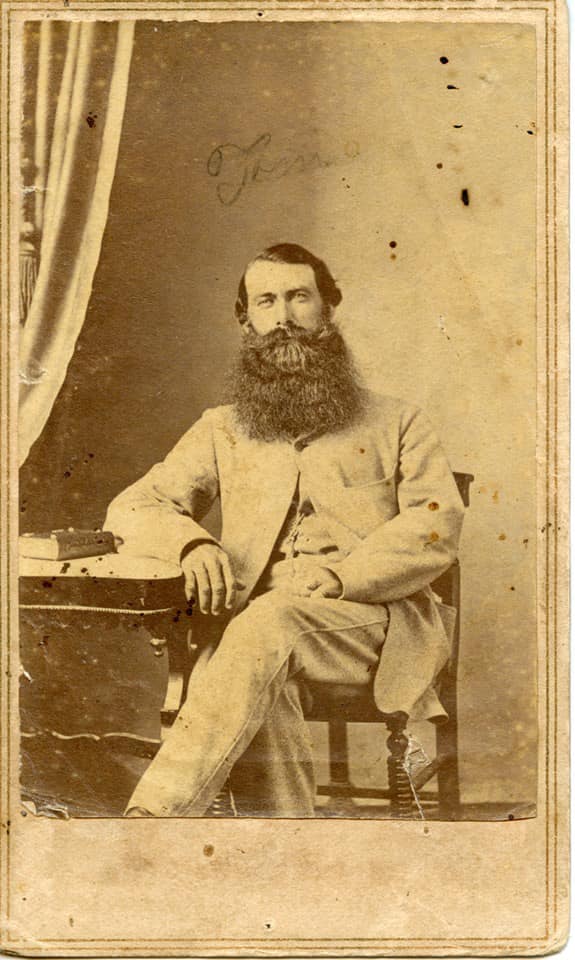

George Washington Davis of North Carolina (1832 – circa 1900)

G.W. Davis was born into a seafaring family near Shackleford banks, Carteret County, North Carolina, in 1832. Little is known of his early life until he appears as the 2nd Mate of the iron-hulled paddle steamer, Britannia, which had been launched from Scotland in the spring of 1862. The Britannia made six runs through the blockade before being captured off of the Bahamas on June 22, 1863, by the USS Santiago de Cuba. Davis, along with many of his fellow crew members, were sent to Fort Lafayette, NY; and later transferred to Fort Warren, Boston, Massachusetts, in September of 1863. Davis remained imprisoned at Fort Warren for the remainder of the War and after, until June 20, 1865.

This CDV of G.W. Davis was taken by photographer J.W. Black, Boston, Massachusetts, during his imprisonment at Fort Warren. Black also appears in several of the group images of Fort Warren prisoners that have been published.

After the War, Davis settled in Smithville (now Southport), North Carolina, where he married, raised a family, and continued in maritime pursuits as a sailor and pilot. He died prior to 1900.

George E. Lyell of Virginia (1837 – 1868)

A native of Norfolk, Virginia, George E. Lyell had been a member of the 54th Virginia Militia before he enlisted as a Private in Captain Nathan W. Small’s Signal Corps Company on March 5, 1862. This Company ultimately became a part of Major James F. Milligan’s Independent Signal Corps, operating as scouts and signal officers along the James and Appomattox rivers. Lyell was present with his company, and primarily stationed in Petersburg, until detailed in 1864 for signal duty to Wilmington, North Carolina, where he would serve on ships intended to run the blockade. Although the particulars of this service are unknown, he does appear on a list of Confederates in Havana, Cuba, in April of 1865, and later back in the Confederacy, where he was paroled at Charlotte, North Carolina, on May 4, 1865.

After the War, Lyell operated a restaurant and saloon in Norfolk, until an untimely death on July 23, 1868.

The CDV of George E. Lyell was photographed by A. Hobday & Co., Norfolk, Virginia, circa 1866-1868.

(These images are in the collection of and are courtesy of Fred D. Taylor.)