Since returning from some travels this week, I have had history “on the brain,” and I have simply wanted to research and write. So with this month honoring women, a recent addition to my “caretaking family” was immediately on my mind. Here’s the rest of the story…

When it comes to collecting old photographs, finding one that is identified is usually about a fifty-fifty shot (maybe less?) It seems to become even more difficult the older the image may be. When a photograph appears that checks the boxes for time period, identification, location, and even more, you have truly been fortunate.

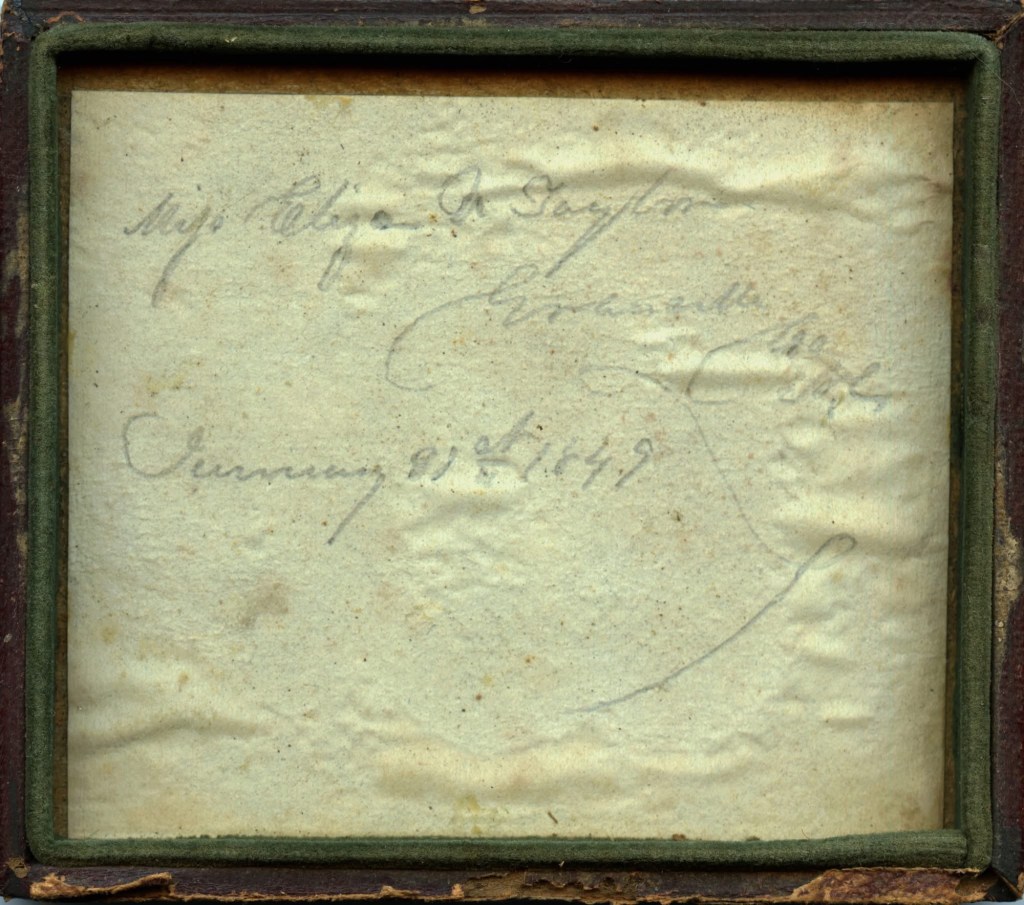

I first saw this daguerreotype a few months back. Candidly, her beauty is what initially struck me. Followed by the photographer’s artistry. I wanted to know more. It had come up for sale from an image dealer, but I missed the purchase by literal minutes to another. Opportunity came to me once again though, and whether serendipity or pure luck, I was able to acquire it – thanks to my friend Ben Rollins.

But the story of this image went much deeper. It was inscribed. It was identified. It had provided a location. It had a date. It was my unicorn.

Meet Eliza V. Taylor. Yes, Taylor.

Eliza was born in 1830 near Oxford, in Granville County, North Carolina, the oldest child of John Camillus Taylor (1800-1873) and his wife Emily Elizabeth Tillinghast (1807-1841). Without a doubt, Eliza was born into a family of privilege. Her father, John C. Taylor, boasted lineage from the prominent colonial Taylor family that produced two Presidents and a signer of the Declaration of Independence; he was a graduate of the University of North Carolina, a prominent merchant, farmer, educator, active in the Whig party and as such, a member of the state legislature in both the House and Senate. Her mother, Emily Tillinghast, was similarly well-situated, being descended from a noted Rhode Island family. Tragically, she passed away when Eliza was just eleven years old, herself at the young age of 34. John C. Taylor remarried though, and Eliza was raised predominantly by her step-mother throughout her teenage years.

Along with her siblings, Eliza was given the foremost education and cultural opportunities. When her father served in the legislature or was otherwise on business travel, she would frequently accompany him to the capital at Raleigh. It was likely during one of these trips to the “big city” that this photograph was taken, and is possibly the work of daguerrean artist John C. Palmer. The image is dated January 31, 1849, when Eliza was 18 years old.

Unfortunately, this story ends on a sad note just a few years later. Eliza passed away on April 3, 1852, from what was described as a “protracted illness.” Though in the prime of her life and taken at the young age of 22, I hope this brief tribute will help to carry on her memory and story. In so doing, I conclude with the following. Eliza (and her family) were active members of St. John’s Episcopal Church in Williamsboro, now in Vance County. It was the Rector of that Parish who penned her obituary. He described Eliza as:

“…dedicated in faith to God” from an early age, and “as a daughter, she was all that parents could ask, affectionate, tractable, cheerful, and ever ready to ‘do what she could’ for the happiness of all around her; as an elder sister her example was most salutary; as a friend she was constant and sincere. Admired and beloved she nevertheless preserved the simplicity, candor and guilelessness of her character unimpaired, she was kind and tender-hearted, yet firm, cheerful and buoyant in spirit, yet innocent and discreet; she had ever an ear for the tale of woe, a tear for scenes of distress, a heart to respond to the call of want… she had among those of her own youth, few peers, and no superiors.”

One could not have ever asked to have fulfilled such a complete life.